How the Grid System in Manhattan Became What It is:

A Historical Google Black Hole Found After 3 Mezcal Cocktails on a Thursday Evening

I know – nothing, truly nothing, is quite as titillating as talking about how Manhattan went from some amorphous mess of hilly farms into the *almost* laser accurate grid system we have today but since there’s actually nothing else to talk about, buckle up.

Between online shopping and writing long form letters to pen pals, I stumbled upon this extremely well-done interactive site, which brings you through the creation of Manhattan’s grid with seemingly endless information and photographic evidence. Below I’ll give you the SparkNotes version of this engineering feat, as it’s mind-boggling to comprehend how they logistically pulled this off. Please, please explore more for yourself though.

Before the grid, New York was structured a lot like Boston – zero order with patches of farms, meadows, and marshes, all laced together with rambling country roads. As the city began to urbanize and haphazard slums like Five Points started to sprout up, Grid Commissioners kicked into high gear and produced a plan in 1811, leveling much of the city topography and creating a uniform ordering system, reworking all existing properties.

The biggest miracle of the 1811 plan was that it was enforced. It took 60 years to complete from 155th Street down, through countless administrations. One of the hardest elements of the plan was tackling Manhattan’s naturally hilly topography, made mostly from the notoriously hard-to-cut rock of the Manhattan schist.

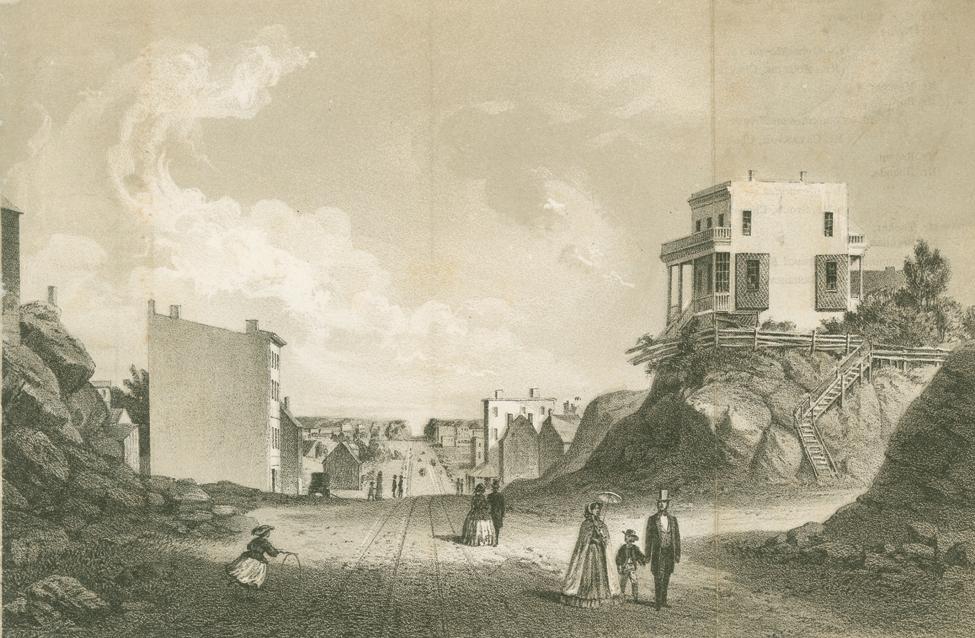

The top photo from above shows the difficulties posed by the bedrock, from W 106th looking north. In the bottom from above, you’re looking north at the intersection of East 42nd Street and Second Avenue in 1861, where the avenue had been laid out, but the surrounding hills were not yet leveled to align with the street grade. Elevations near the intersection of First Avenue and 41st Street dropped nearly 40 feet as a result of street construction, and some elevations on the West Side changed by as much as 118 feet.

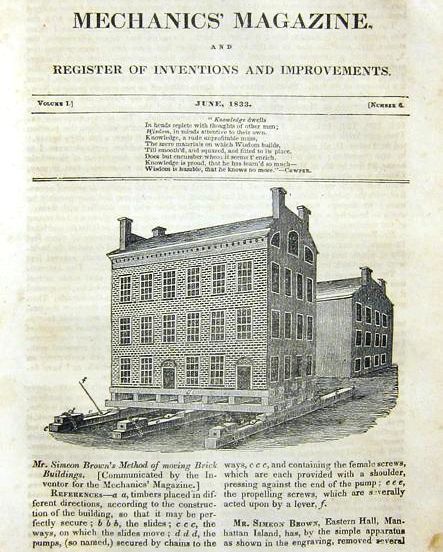

If a house stood in the way of a new or widened street, the City Corporation forced the owner to remove it. Houses of little value were torn down, but some owners of more expensive dwellings elected to move their houses, in their entirety, to new sites.

Almost halfway into the grid project, commissioners realized the severe lack of public areas, which lead to Union Square, Gramercy Park, Washington Square Park, and Central Park. The plan strategically implemented parks throughout the city to force those properties facing the park to pay higher property taxes. Side note: a lot of corrupt politicians gobbled up properties they had inside knowledge that streets and avenues would be carved through; they did this to command the inflated price the city was willing to pay for the sliver being made into a roadway.

Sidewalks were the invisible third element of the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811. The two rules for sidewalks held that: 1) the width of the sidewalk must correlate with the width of the street 2) property owners must construct and maintain their sidewalks. As the grid began to fill out, its long axial streets provided the perfect setting for bourgeois Manhattanites to promenade. In 1887, The New York Times reported that “Fifth-avenue, the best cleaned street in the city, is the favorite promenade”. In the photograph above from 1898, well-dressed pedestrians pass each other on the broad sidewalks alongside Madison Square Park

Please, please keep reading for yourself…

Because once you finish “Tiger King”, you’ll need something else to pass time.