“A Coop Is Like a Condo Except Your Neighbors Are Completely Insane and They Also Interview You, Right?”

^ me, trying to sound cheery while announcing to my buyers the next horrific step on deck in their quest to purchase a coop

“Oompa loompa doompety doo

Is this medieval and antiquated form of ownership for you

Oompa loompa doompety dee

Well, it doesn’t really matter if it’s the UWS/UES/WV/GV/Soho/Gramercy/Park Slope/Cobble Hill/Fort Greene/Carroll Gardens/Boerum Hill/Prospect Heights where you want to be

What will your future neighbors think of your detailed financial spreadsheet

Peppering you with questions on it while you’re in the interview hot seat

There’s no way of escaping this archaic purchasing format

If you want to receive the coop’s welcome mat

Literally *no one* cares if you don’t like the look of it

Oompa loompa doompety da

Prepare to temporarily kiss your sanity au revior

But once you’re approved you can throw a coup

Like the Oompa Loompa Doompety do”

Whenever I try to explain coops to anyone outside of New York, I usually compare it feudalism in 12th century medieval Europe, that terrifyingly lawless period in history that we spent way too much time in school studying, instead of learning how to code or to prepare our taxes. Buyers looking to enter a coop’s milieu are, for all intents and purposes, serfs. Nothing more than a peasant at the mercy of the property-owning nobles, who take this military form of hierarchy with the utmost seriousness.

*Coaching my buyers for their board interview*

Me: Whatever you do, please do your best to come off as reserved, calm, respectful, quiet, responsible, mellow, and low-key.

My buyers:

Obviously this is me exaggerating solely so I can build out a dramatic analogy, but since coops illicit the same reaction as when Voldemort’s name is uttered in Harry Potter, let’s review this often-feared ownership type and repaint coops in a marginally better light.

In Manhattan, cooperatives have been the traditional way to own for nearly a century and comprise at least 60% all apartments available for purchase. Unlike the traditional ownership most people think of, coops are owned by an apartment corporation, not by an individual. Because you don’t technically “own” the specific unit, the board does have rules they enforce, that can range from laissez faire to extremely restrictive. It’s basically the building’s way of controlling who is allowed to purchase/sublease in the building and the general discourse of the building itself.

When you purchase an apartment in a co-op, you are buying shares of the cooperative that entitle you, as a shareholder, to a “proprietary lease.” This proprietary lease is for a specific unit in the cooperative, to which you are a “tenant”. Typically the larger your apartment, the more shares of the cooperative you own. The wonderful thing about coops is that since you’re not buying “real property”, you don’t have title, WHICH means you don’t have to pay the hefty mortgage recording tax and title insurance that condos have to at closing.

Co-op shareholders pay a monthly maintenance fee to cover building expenses like heat, hot water, insurance, staff salaries, real estate taxes, and the mortgage debt of the building. Portions of the fee are tax deductible, as shareholders can deduct their share of the building’s real estate taxes, which is important to note when assessing carrying costs for comparable condos. This maintenance fee can increase 3-7% annually and the board can require you to pony up money for the reserve or for a particular project in the building

Purchasing a co-op can be an intricate process and subletting can be challenging. Each co-op has its own rules, which should be considered prior to purchasing. Approval to purchase shares of a co- op must be granted by a board of directors, who also have the authority to determine how much of the purchase price may be financed and minimum cash requirements.

Co-ops generally allow a maximum of 75-80% financing, but that can shrink to 40-50% in some more restrictive buildings. Co- ops will also scrutinize the buyer more so than condos and have guidelines for financial qualifications to purchase. Typically, the co-op would like to see that the buyer has two years of maintenance and mortgage fees liquid after all closing costs and down payment are accounted for. They would also like to see that the buyer’s debt-to-income ratio is 29% or less.

All prospective purchasers must submit a “board package” containing a purchase application, personal and professional letters of recommendation plus detailed information on income and assets. The board will also require an interview so they can meet the applicant and ask any questions regarding the information provided in the board package. They can approve or deny any applicant without stating a reason and their decision cannot be challenged in a court of law.

Owners are typically restricted in subletting – ranging from as lenient as unlimited after two years of ownerships, to subletting is allowed 2 out of every 5 years, to 2 years total in ownership, to case by case, to no subletting at all. The board also charges you a fee for subletting and has to approve your tenant. Yet again, it’s the board’s way of controlling who lives in the building.

Co-ops vary building to building regarding what purchasing structures they allow and have the ability to say no to purchasing types like parents buying for children, pied-à-terre, co-purchasing, and gifting.

Transactions can take between 3-6 months, depending if you’re buying all-cash (a bit faster) or if you’re financing (a tad longer), padding that time frame with board package compilation, board package review, interview scheduling, and just all the delays and absurd amounts of time it takes for the managing/transfer agent to complete seemingly easy steps.

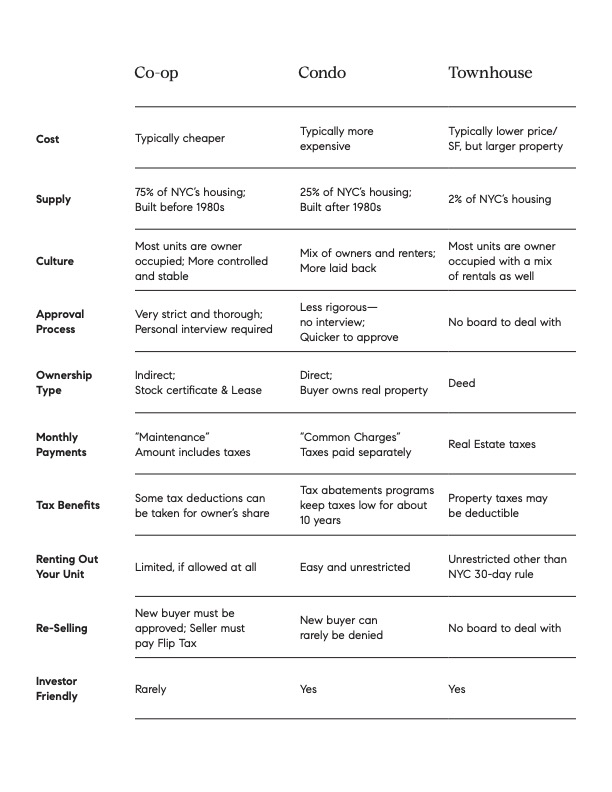

In a more digestible piece, see below for the high level difference between coops, condos and townhouses: